Song is alpha quality and is not intended for production use.

Song

Song is a terse functional programming language.

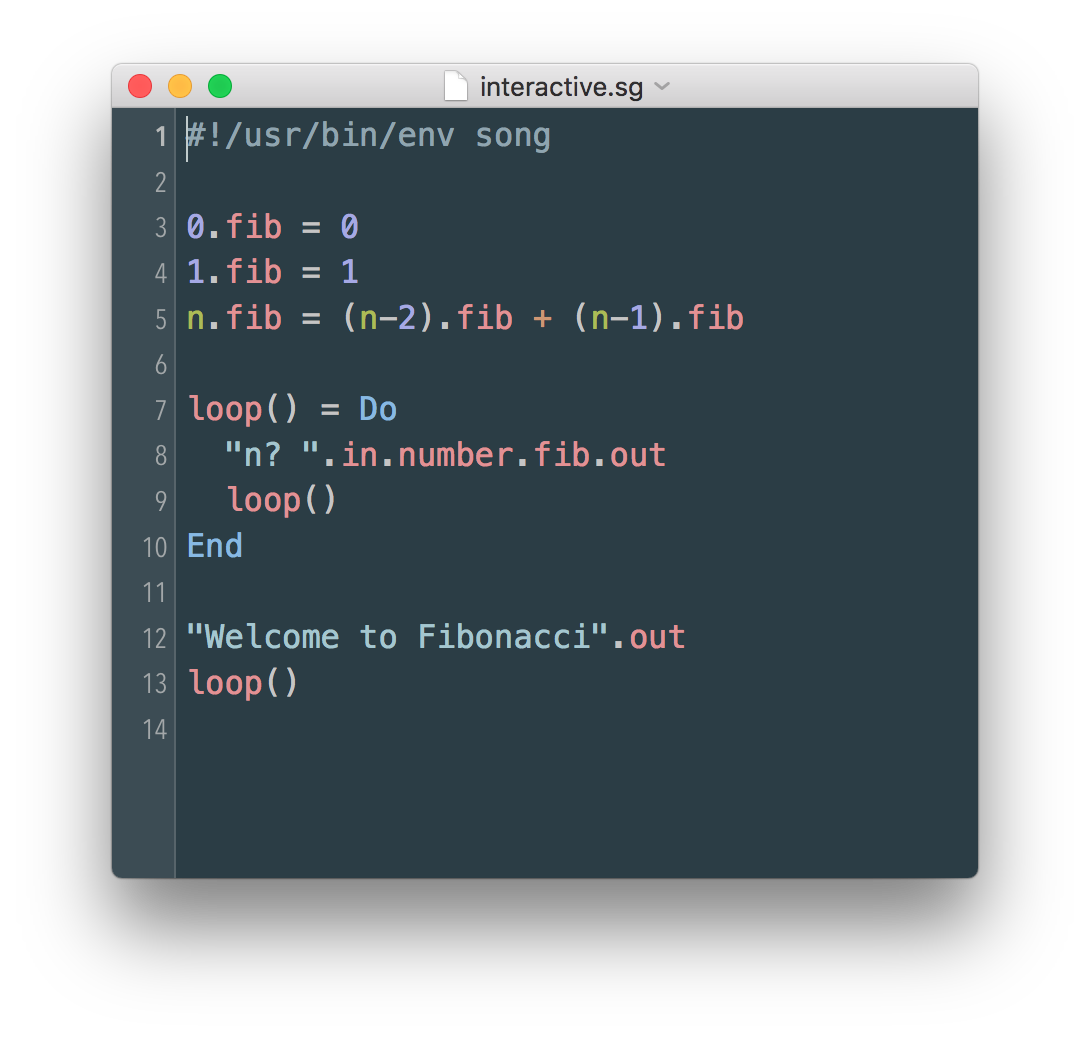

Here’s a program that calculates Fibonacci numbers:

#!/usr/bin/env song

0.fib = 0

1.fib = 1

n.fib = (n-2).fib + (n-1).fib

loop() = Do

"n? ".in.number.fib.out

loop()

End

"Welcome to Fibonacci".out

loop()

Song has no if statements and no loops. Instead, you use pattern matching and recursion (tail calls are optimised). There are no reference types: everything is a value.

Here are some more complex examples:

# Drop the first n items from a list

list.drop(0) = list

[x|xs].drop(n) When n > 0 = xs.drop(n-1)

[1, 2, 3].drop(1)

# [2, 3]

# Take the first n items from a list

list.take(0) = []

[].take(n) = []

[x|xs].take(n) When n > 0 = [x] + xs.take(n-1)

[1, 2, 3].take(2)

# [1, 2]

# Extract a slice from the middle of a list

list.slice(i, n) = list.drop(i).take(n)

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].slice(1, 2)

# [2, 3]

# Reverse a list

[].reverse = []

[x|xs].reverse = xs.reverse + [x]

[1, 2, 3].reverse

# [3, 2, 1]

# Push and pop items from the end of a list

list.push(x) = list + [x]

list.pop = list.pop(1)

list.pop(n) = list.reverse.drop(n).reverse

[1, 2, 3].push(4)

# [1, 2, 3, 4]

[1, 2, 3].pop

# [1, 2]

Using Song

You can use Mint to install Song:

mint install dcutting/Song

You can use the Song REPL from the command-line to play around:

$ song

Song v0.1.0 🎵

>

Use the --verbose flag to get additional AST dumps when things go wrong in the REPL. Use CTRL-D to exit.

There are also a few extra commands for use inside the REPL. Type ? to get a dump of the current context (declared variables and functions), and ?del SYMBOL to delete symbols from the context. This will save you restarting the REPL when you add things you didn’t mean to.

Song v0.2.0 🎵

> x = 5

> ?

{

x = (

5

);

}

> ?del x

> ?

{

}

>

You can also run Song scripts:

$ song fib.sg

And you can put a shebang at the top of your script to run it directly (don’t forget to chmod your script to make it executable):

#!/usr/bin/env song

0.fib = 0

1.fib = 1

n.fib = (n-2).fib + (n-1).fib

out(7.fib)

Types

Booleans

The boolean literals are Yes and No. Song has the standard logical operators:

Yes And No

# No

No Or Yes

# Yes

Not No

# Yes

Numbers

Song numbers can be integers or floats. You can do arithmetic with them as you’d expect:

5 + 4 * -2

# -3

(5 + 4) * -2

# -18

3.4 / 2.0

# 1.7

If you mix integers and floats in your arithmetic, you’ll always get a float result:

5 + 1.2

# 6.2

And if you divide numbers, you’ll also get a float:

5 / 2

# 2.5

If you want to do integer division, use 5 Div 2 and 5 Mod 2 (but using those with floats will cause an error).

Floats can be converted to integers with the built-in truncate function:

5.4.truncate

# 5

5.9.truncate

# 5

-3.9.truncate

# -3

-3.1.truncate

# -3

You can compare numbers:

4 Eq 4 # Yes

4 Neq 4 # No

4 > 2 # Yes

4 < 2 # No

4 >= 4 # Yes

4 <= 3 # No

But you cannot test floats for equality, since floating point numbers are imprecise:

4.0 Eq 4.0 # error

4.0 < 5.0 # Yes

Lists

Lists are how you combine simple values into more complex values. Items can be different types:

[] # Empty list

[1, 2, 3]

[Yes, 1, 2.3]

You can nest lists:

[[1, 2], [3, 4]]

You can concatenate two lists with the + operator:

[1, 2] + [3, 4]

# [1, 2, 3, 4]

You can also use the “list constructor” syntax to insert items at the beginning of a list:

x = [3, 4]

[1,2|x]

# [1, 2, 3, 4]

The Eq/Neq operators work for lists too:

[1, 2, 3] Eq [1, 2, 3]

# Yes

Characters (and Strings)

Individual character literals look like this:

'A'

'$'

'\''

'\\'

You can’t do much with characters by themselves, but when you put them into a list Song interprets them as strings:

['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']

# "hello"

And you can use the string literal syntax as shorthand to create strings:

"hello"

# equivalent to ['h', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o']

Because strings are just lists of characters, you can also concatenate them and test them for equality:

"hello" + " world"

# "hello world"

"hello" Eq "world"

# No

If you have a number represented as a string, you can use the built-in number function to convert it to a number:

x = "99"

x.number

# 99

y = "-3.1"

y.number

# -3.1

But this will throw an error if your string cannot be converted to a number.

Variables

You can assign values to variables:

x = 5

y = 9

z = x < y

Names must start with a lowercase letter (or an underscore), followed by any combination of lowercase/uppercase letters or digits. You can also use underscores and question marks. Names like this are valid:

x

_x2

numberOfApples

visible?

But these aren’t:

7names

BigName

symbols@

Functions

Functions can be written and called using two equivalent syntaxes: “free” or “subject”.

Free functions have all parameters and arguments in parentheses after the function name.

Subject functions have the first argument appearing before the function name with dot notation.

These function declarations are equivalent:

inc(x) = x+1

x.inc = x+1

x.inc() = x+1

Note that in the subject syntax, the parentheses are optional if there’s only one parameter.

These function calls are also equivalent:

inc(5)

5.inc

5.inc()

Again, the parentheses are optional for the subject syntax.

You can mix the different syntaxes for declaring/calling functions:

inc(x) = x+1

5.inc

# 6

Functions that take more than one parameter look like this:

plus(x, y) = x+y

x.plus(y) = x+y

plus(3, 4)

# 7

2.plus(3)

# 5

If you’re allergic to parentheses, the subject function syntax is convenient for chaining together multiple function calls. These expressions are equivalent:

plus(inc(fib(5)), 10)

5.fib.inc.plus(10)

The names of functions follow the same rules as variables:

x.even? = x Mod 2 Eq 0

Patterns

Song uses pattern matching to decide which function to call, and as a way of binding arguments to parameters.

You’ve seen simple patterns already:

x.inc = x+1

This function will match any argument passed to it, and bind it to the variable x.

You’ve also seen literal patterns:

1.fib = 1

This will only match calls where the argument is the value 1:

1.fib

# 1

(2-1).fib

# 1

2.fib

# error, no match found

Note that since floats cannot be tested for equality, you cannot use literal floats in patterns.

To do more powerful computation, you can use the list constructor syntax to destructure lists into a head and tail:

[x|xs].head = x

[5, 6, 7].head

# 5

[x|xs].tail = xs

[5, 6, 7].tail

# [6, 7]

In cases where you only care about part of the pattern, you can use underscores to ignore other matches:

[x|_].head = x

[5, 6, 7].head

# 5

If you want to match more than just the head, you can add more parameters:

[x,y|xs].second = y

[1, 2, 3].second

# 2

With list destructuring, you can write functions that process entire lists. This function calculates the length of a list:

[].length = 0

[_|xs].length = 1 + xs.length

[5, 6, 7].length

# 3

Because strings are just lists of characters, you can use list destructuring to process strings too:

"hello".length

# 5

And patterns can be nested as needed for more complex matches:

[[], []].zip = []

[[x|xs], [y|ys]].zip = [[x, y]] + [xs, ys].zip

[[1, 2, 3], ['a', 'b', 'c']].zip

# [[1, 'a'], [2, 'b'], [3, 'c']]

If you use the same variable name several times in a pattern, the values that match must be equal:

list.startsWith?([]) = Yes

[x|xs].startsWith?([x|ps]) = xs.startsWith?(ps)

_.startsWith?(_) = No

"hello".startsWith?("he")

# Yes

If the values that match a repeated variable are floats, Song will throw an error because floats are not equatable.

When

Sometimes you need a bit more discrimination than pure patterns can provide. The When clause applies an additional constraint on a function that a caller must match.

This function takes a list of numbers and returns those that are more than some argument:

[].moreThan(_) = []

[x|xs].moreThan(n) When x > n = [x|xs.moreThan(n)]

[_|xs].moreThan(n) = xs.moreThan(n)

Pattern matching is performed in the order the function is declared. The first match found will always proceed, so you need to declare your more specific cases above your more general cases.

Lambdas

Not all functions need names. Lambdas let you make anonymous functions that can be passed around as values to other functions.

This function apply expects a function f that takes one argument. It then calls that function using the other value it’s been given:

x.apply(f) = f(x)

5.apply(|a| a*2)

# 10

Note the lambda syntax uses pipes | to specify parameters. They also support some pattern matching, which is useful for destructuring list arguments:

x.apply(f) = f(x)

[1,2,3].apply(|[x|_]| x)

# 1

They don’t support pattern matching simple literals like numbers though, since this would not be a very useful feature.

Lambdas don’t just have to be passed as arguments to other functions. They can also live on their own in a variable:

double = |x| x*2

double(5)

# 10

Or you could store them in a variable, and use that variable when a lambda is expected:

x.apply(f) = f(x)

double = |x| x*2

5.apply(double)

# 10

You can even treat them as “literal functions”:

(|x| x+1)(5)

# 6

As with named functions, you can call lambdas using free or subject syntax:

double = |x| x*2

double(5)

# 10

5.double

# 10

Lambdas can have as many parameters as you like, separated by commas:

lessThan = |x, y| x < y

lessThan(4, 5)

# Yes

Although unusual, you can even make lambdas with no arguments using the double pipe syntax:

x = || "hello"

x()

# "hello"

Anywhere you can pass a lambda as an argument, you can also pass a named function:

[].length = 0

[_|xs].length = 1 + xs.length

x.apply(f) = f(x)

[1, 2, 3].apply(length)

# 3

Do/End scopes

Sometimes you want to break your functions into a few statements to make them easier to read. You can do this with scopes:

[].sort = []

[x|xs].sort = Do

left = xs.select(|k| k < x)

right = xs.select(|k| k >= x)

left.sort + [x] + right.sort

End

Scopes evaluate each expression in their body, but only return the result of the last one.

You can also write scopes on one line using commas:

x.inc = Do y = x+1, y End

As you can see above, you can declare things inside scopes; in fact this is the main reason to use them.

But it’s worth noting that if the last statement in your scope is a function or variable declaration, it will be exported out of the scope for use in subsequent code:

Do

foo = 99

End

foo

# 99

If the declaration is not the return value of the scope, then it will be local to the scope only:

Do

foo = 99

foo + 1

End

foo

# error, unknown symbol

If your scoped declaration has the same name as an existing declaration outside the scope, the outer one will become unavailable within the scope:

foo = 99

Do

foo = 45

foo

End

# 45

But if the scope’s return value is a declaration of a new clause for a function that already exists, Song will combine the clauses into the same function:

x.size When x < 10 = "small"

x.size When x < 100 = "large"

1000.size

# error

Do

x.size = "enormous"

End

1000.size

# "enormous"

This may or may not be what you intend. In general, it is easiest to reason about scopes that don’t shadow existing declarations.

Input and output

You can print things to stdout and stderr using the out() and err() built-in functions:

out("hello", "world", 99)

# "hello world 99" to stdout

err("uh oh")

# "uh oh" to stderr

Reading a line of input from stdin is similarly straightforward:

name = in("What is your name? ")

out("Hello", name)

You can make a simple interactive loop using recursion. Here’s that Fibonacci program again. The loop() function never exits, so it continues to ask the user for another number:

#!/usr/bin/env song

0.fib = 0

1.fib = 1

n.fib = (n-2).fib + (n-1).fib

loop() = Do

"n? ".in.number.fib.out

loop()

End

"Welcome to Fibonacci".out

loop()

Song automatically detects tail call recursion like this and ensures new stack frames are not created for each iteration of the loop. More generally, this means your functions can recurse to any depth when written in tail call style.

Scripts can also read arguments from the command-line passed in the args variable. The first argument will be the name of your script, so you’ll usually want to read the second one:

#!/usr/bin/env song

[_,b|_].second = b

x.double = x*2

args.second.number.double.out

$ ./doubler.sg 9

18

Song cannot currently read input from files, so you’ll need to include most data in your script. But I’m working on it. ;)